I remember the night I got back to my room after seeing Aunt Esther and leaving with the envelope of letters. I sat on the hotel bed and went through the contents, letters and pictures, reading a snippet from one letter, looking at a few photos at a time, and ultimately finding the map.

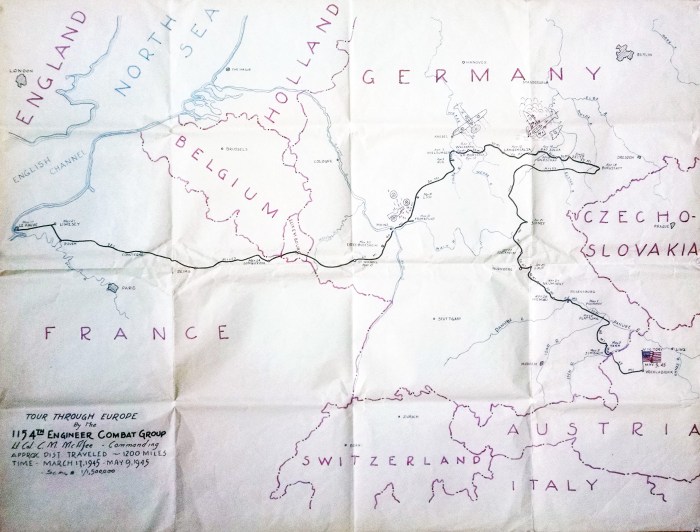

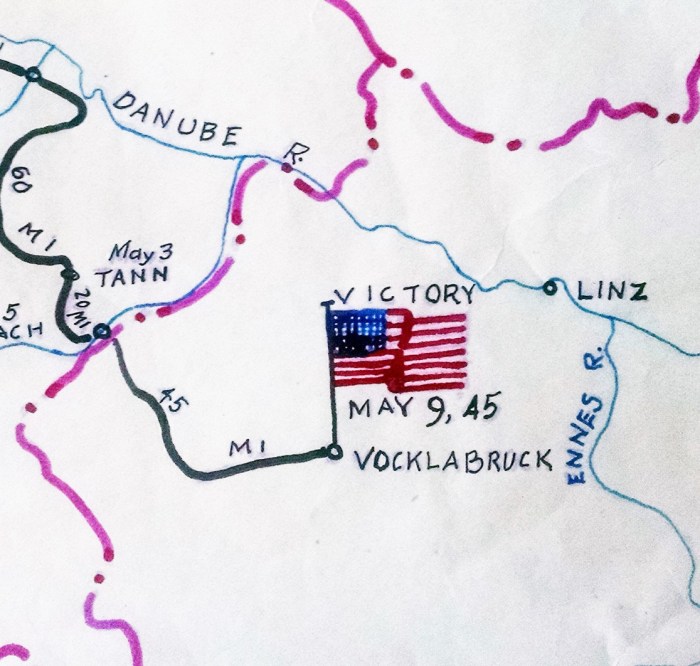

I was surprised by how many times I had to unfold it before it was fully laid out before me. At 30 by 24 inches the map was the largest item in the envelope.

My earliest reaction to seeing the map and then studying it more carefully was: Wow, my father made that? I assumed that as an engineer and draftsman this was something he was capable of making even though I had never seen a project like this from him when he was alive. I thought: Wow, he can draw too?

Then, not so odd for me, I tried to imagine what this original creation by my father would look like framed.

I also remember wondering if any of the towns he marked on the map were also the marks for, or somewhere near, the concentration camps the U.S. Army liberated, and if the dates on the map near those camps actually matched up with the actual liberation dates for those particular concentration camps. Further, I wondered if any of Solly’s letters which corresponded to those actual liberation dates contained any mention of his experiences in liberating two or three of those camps – something I already knew to be true for my father.

That narrative, about entering the concentration camps and being rushed for food, had always been a central part of my memories regarding my father’s stories about WWII. He was there and he showed me pictures. The morning after my Bar Mitzvah was the first time he showed me those pictures, taking me downstairs, opening a small shoe box and removing a handkerchief wrapped around a dozen photos. I remember them: pictures of standing skeletons with huge eyes, a pile of dead bodies stacked up on top of one another in a clumsy and haphazard way, a group of three men with a young boy who seemed to stare up at Solly’s camera.

They had a tremendous impact and although I hadn’t thought about them in years the night I first looked at the map I knew right then that I had to go back to my mother and see if she and I could find those pictures. (Read more about the Real Holocaust pictures in the Real Holocaust post(s).)

I also remember seeing the word DESTINY with a big ? after it flash through my mind, or why else would it turn out that the reason I was even able to visit Esther and Mike in NYC that fall of 1999 was because I was neck deep in the final few months of producing and directing Awake and Sing by Clifford Odets, which was a play about a mostly secular Brooklyn Jewish family in the early 1930’s. Mysteries everywhere.

During my eventual dinner with Mike, and the visit with Esther a few weeks later when I believe I got the letters, they told me a number of things that blew my mind as much as the letters, maps and photos had done including: their separate and equally compelling memories of sitting in the back row of the Yiddish theatre; Esther telling me about seeing the Dybbuk and remembering her feelings of the experience, the sounds and gasps of the audience around her, holding some adults hand (maybe her mother’s) and the lighting and stage effects that left a clear image in her head; and Mike describing a play he saw by the Group Theater in the 1930’s, which after hearing him tell me the story happened to be, by my reckoning, the original production of Awake and Sing.

There was an interesting idea for me in all this millisecond flash-confluence of things around Sol.

I don’t remember what happened chronologically next with any thing related to the above thoughts, letters and photos. All I remember is that a year or so after I moved to Key West and finally went to find the map I couldn’t.

Then I found it again a few years later; then lost it; and found it more recently. The original concentration camp photos had an even more bizarre journey and at this writing still remain lost, if they ever existed in the first place. All of this is a much longer story which itself is still fogged out in between my personal gaps between memory and history.

However, with the recently mentioned resurfacing of the map, and Stacey’s equally recent discovery of the Holocaust postcard/photos in 2015, I was able to finish up enough loose ends and complete this Love Solly blog.

The only remaining question before I could publish the blog centered around the Map. Who really made it? Was it Solly as I had always assumed and accepted? I had to bring it back to Selma and push her for a verdict.

- There is no date on the map so when did Solly do it?

He couldn’t have done it while he was fighting his way across Germany. Logically, he would have had to fashion it after he came home. - Where did he get the town names and dates, since there was no way he kept a diary with that information?

He was probably able to get the data and mileage from Army records; they printed out a lot of material during and after the war and still have an immense archive. - Drawing a route across a map is one thing but drafting a regional world map to scale? With some research I ultimately recognized this very same country/region map as the underlay of other Army battle maps from WWII which would explain the country borders and labeling if Solly had purchased a copy.

- So what if it doesn’t look like his handwriting ? Again, Solly was a draftsman so I was mostly convinced before I went to see Selma that Solly could have marked the combat route and the towns, and created the small illustrations and main key with its description.

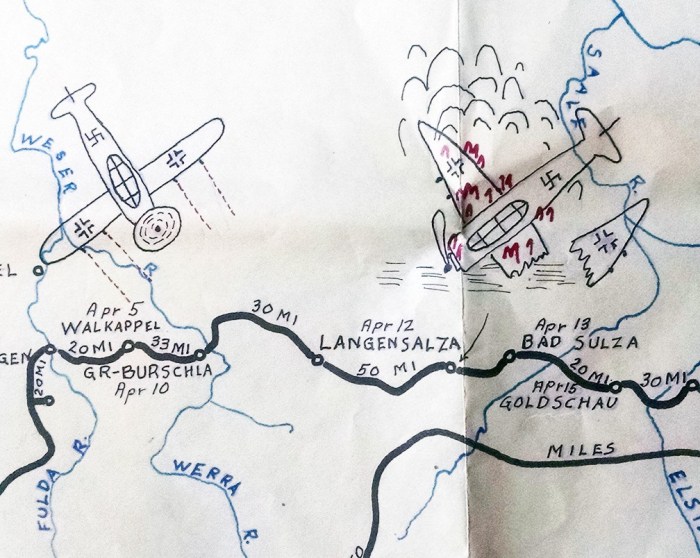

- Perhaps he could draw when he was drafting? The illustrations look like they were hand done. They are not as finished as the rest of the map and therefore, even though I never saw my father draw or sketch anything, he had to have the ability to make a blown up jeep, a German plane, and an American flag as basic in nature as the drawings on the map.

- So who else knew about his map? This was a vexing problem. About 3 or 4 months after I first received the map I finally got around to asking both Esther and Mike about the map: had either of them ever seen it? They both said no. If Solly had in fact made this map it would have been a big project. How come no one remembers it or seems to have been shown the map? After work like this why wouldn’t he have shown it to someone?

Selma passed her judgement in seconds, never hesitating from the first: “There is no way he [Sol] could have ever made something like this.”

THE MAP OF BATTLES

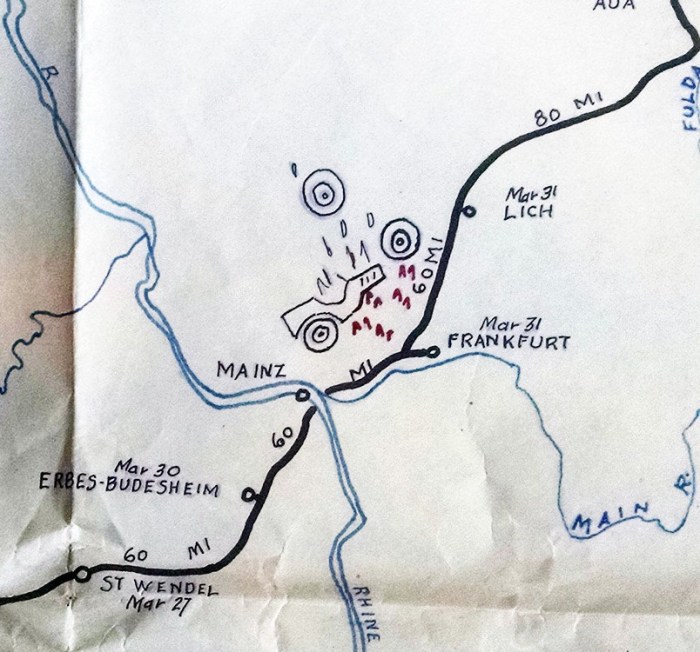

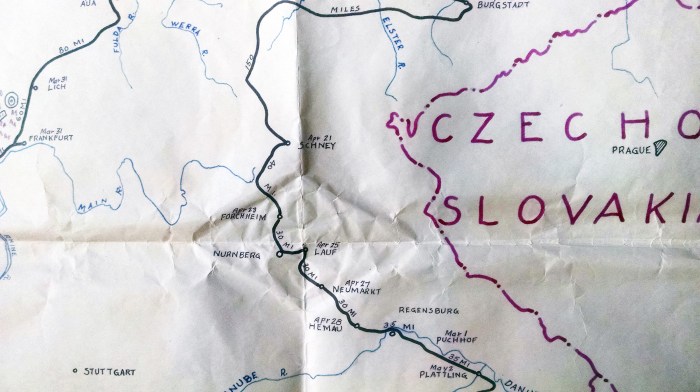

The Map was also helpful in nailing down the exact company, sub-company, and divisional unit Solly was in, and perhaps, any larger military campaigns that his route showed he would have participated in. Taking the U.S. Army Battle Campaign map for “The Encirclement of the Ruhr Valley, March-April, 1945”, and overlaying Solly’s Route Map for the 115 4th Engineers shows how he was thick in the middle of those doings. It is said that the winter months through April in 1945 Germany were brutal for U.S. troops.

Solly was in Patton’s 3rd Army which, as this map indicates, were credited for major campaign victories in Normandy (with Arrowhead), Northern France, The Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe.

In WWII a US Army infantry regiment consisted of approximately 3000 men. The Infantry Division was based around three infantry regiments, Solly and the 115th being one of them. A full Army like the 3rd Army also included 3 regiments and artillery and support units totaling 15,000 men overall.

Other U.S. Army Stats and Divisional Information for Solly’s Units:

4th Combat Engineers with 4th U.S. Infantry Division, “Ivy”

- Arrived European Continent (D-day) 06.06.1944

- Entered Combat – 06.06.1944

- Days in Combat – 299

- Prisoners of War Taken – 75,377

- Killed – 4,488

- Wounded – 16,985

- Missing – 860

- Captured – 121

- Battle Casualties – 22,454

- Non-Battle Casualties – 13,091

- Total Casualties – 35,545

29th US Infantry Division “Blue and Gray”

- Entered Combat (Entire Division) 07.06.1944

- Days in Combat – 242

- Prisoners of War Taken – 38,912

- Killed – 3,720

- Wounded – 15,403

- Missing – 462

- Captured – 526

- Battle Casualties – 20,111

- Non-Battle Casualties – 8,665

- Total Casualties – 28,776